Ageing Baby Boomers have been blamed for the looming crisis in healthcare demand. But it won’t end with their demise – in fact, it will only get worse.

There is no doubt the “silver tsunami” of ageing Baby Boomers will stretch the Australian healthcare system to its limits and beyond, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves the crisis will be over once the Boomers have departed, says a US expert.

Tadashi Funahashi, chief innovation officer for Kaiser Permanente in southern California, told delegates at the Independent Hospital and Aged Care Pricing Authority’s national conference in Adelaide today that the looming crisis was driving his company to continue to innovate.

“What we call the ‘Silent Generation’ – people aged 75 to 85 – is a relatively small population in the United States, about 14 million, and in Australia, about 1.4 million,” said Mr Funahashi.

“The generation after that, the Baby Boomers, is the largest population, both [in the US and here]. We have about 64 million and I think you have about 2.4 million.

“The generation after that, the Gen-Xers, are the people aged 55-65. We have about 60 million, which is 5-10% lower than the Boomers. And your population reflects that,” he said.

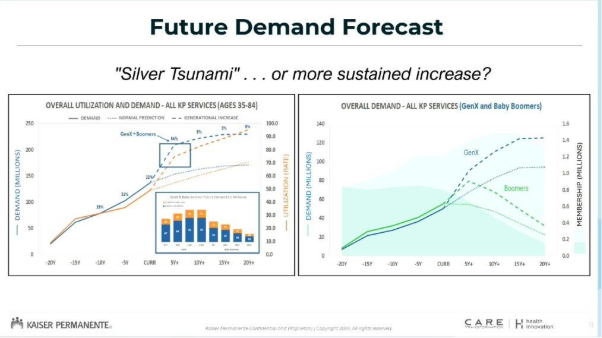

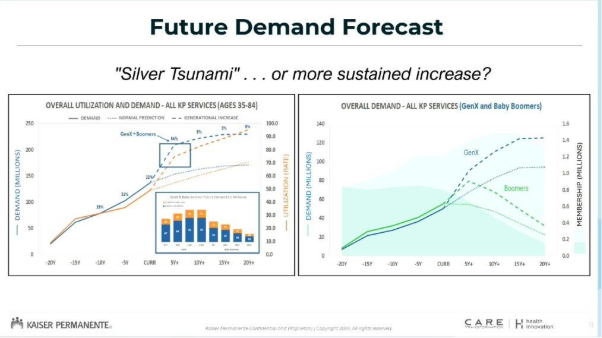

“If you think about what we call the ‘silver tsunami’ – the ageing population of those people who are 65 to 75 – in the US it’s going from 14 million in the Silent Generation to 64 million Baby Boomers.

“Not all those Boomers will make it to that age, but even if you estimate a very pessimistic survival curve of 50%, we will still have more than a doubling of the number of people that are going to be in that age.”

But that’s not the only problem, says Mr Funahashi. Healthcare needs increase significantly as 75-year-olds become 85-year-olds, by about 38%, he said.

“If you think about that alone, a doubling of the underlying population with an increase in their utilisation rate, it is going to be crushing to the United States,” he said.

“We simply don’t have enough resources in terms of human power to take care of those patients.”

But wait, there’s more, and it’s even more frightening.

“We decided to look at data and see what were the demands of that generation when they were 10 years younger compared to the generation that occupies the 10-year younger age today,” Mr Funahashi told the IHACPA crowd.

“If you look at the utilisation rate for the Silent Generation versus the Baby Boomers, we see about a 50% increase in their utilisation. When the Silent Generation were 65 to 75, their utilisation of healthcare services was substantially lower than the Baby Boomers.

“The Boomers are 50% higher.

“What about the Gen-Xers compared to the Baby Boomers? The Gen Xers are generally less healthy than Baby Boomers were at that age.

“When the Boomers were 55 to 65 compared to the current 55 to 65-year-olds, the Gen-Xers have a utilisation rate that’s about 33% higher.

“So even though their numbers are lower by about 10% in the US, their utilisation rate is about 33% higher.”

In other words, even though the silver tsunami is coming, it won’t be a single wave that passes and goes by us.

“It is a sustained increase,” said Mr Funahashi.

“If you then look at utilisation rate against the population, i.e. demand, you can see what our anticipated demand is going to be over the course of the next six to eight years.

“If you continue to do what we’ve been doing, and remember, in the US, we are already [spending] 19.6% of the GDP for healthcare, in Australia, it’s about 10%, that is going to be a crushing blow to the healthcare system, which is already struggling to work with the amount of demand.

“The silver tsunami is not a single wave that passes. The Gen-Xers will continue to add and we’re going to continue to see a dramatic increase in healthcare needs at a time when healthcare is already in a crisis.

“So, what do we do?

“We can’t train our way out of it by having more doctors. We’re going to have to figure out innovative and transformational ways of seeing how we can address this increasing demand.”

Prevention and preventive care is key, said Mr Funahashi.

Related

Kaiser Permanente focuses on what he called “care gaps”. Using its electronic network of information from claims, staff from receptionists on up can see which patients have a gap in what they should be doing in terms of preventive care.

“We generate a report every day, and that comes up on our electronic records,” said Mr Funahashi.

“When somebody interacts with that patient and they have a care gap, it shows up. We let them know, and we get them to try to fill that care gap.

“Not only that, if they haven’t filled the care gap, or if they have and the results are urgent, we have a safety net that then is a closed loop that makes sure, if something comes back positive, that the organisation then acts to intervene, to provide the appropriate care.”

The results, he said, have been significant.

“If you look at the outcomes for cancer, we perform better across the board in cancer survival rate than [anywhere] in the United States.

“People always say preventative care is really important, right? And it’s very hard to argue that staying healthy is better than treating disease, but what is the impact on the enterprise?

“Since we have the information that we’ve gathered on care gaps, what is the difference in future utilisation rate between those people who have completed their care gaps versus those that haven’t.

“Not only are they healthier [but] healthier people do, in fact, lead to lower utilisation rates.

“So, in terms of controlling demand, preventative care by data, by empiric data, works.”

A focus on prevention was a no-brainer for Australia, Mr Funahashi concluded.

“In a country like this, preventative care should be A-1, right?” he said.

“You have the citizens, you have the methodologies.

“So prevention is a really good way to look at making sure that future utilisation is lower and that your population is healthier, and equally importantly, when there is a problem to be solved, integration and coordination of that care is key.

“Fragmentation leads to inefficiencies, whereas coordination leads to better outcomes and far better efficiencies.

“The question is, how to do it in an effective manner?”

The IHACPA national conference is on in Adelaide on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday, 5-7 August 2025.