Non-admitted services can no longer remain an episodic, referral-driven process. It must evolve into a system of dynamic, digitally enabled collaboration.

The Grattan Institute’s 2025 report, Special Treatment: Improving Australians’ Access to Specialist Care provides a sobering yet unsurprising assessment of our current state.

For those working at the coalface, its findings reflect what we already know: patients are delaying or missing out on specialist care because they cannot afford the fees or cannot endure the wait.

As a paediatrician, I am acutely aware of what is at stake.

When a child with developmental concerns, an adolescent with unexplained weight loss, or a young adult experiencing firstepisode psychosis is referred for specialist care, it is rarely discretionary.

These referrals are born from genuine concern. Yet, as the Grattan Institute report highlights, millions of Australians face an unenviable choice — wait months, sometimes years, for care, or pay hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars out of pocket.

Growing gulf in access to specialist care

The report highlights a deeply inequitable system. Wealthier communities receive up to a quarter more specialist services than poorer ones, despite having better overall health. Rural and remote Australians are particularly disadvantaged, with half of these communities receiving fewer than one specialist service per person each year.

In paediatrics, these disparities are amplified.

Children in regional and remote areas present later and often sicker, and families frequently face additional costs for travel and accommodation just to access care.

It is common in most jurisdictions now for paediatric referrals to public developmental and behavioural clinics to have wait times of 18 months to four years. For conditions where early intervention can change a child’s trajectory, such as autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay, these wait times are unacceptable.

Adults are similarly affected.

Wait times nationally for an appointment at a public clinic are often far longer than clinical guidelines recommend. Across Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, and Adelaide, there are 50 specialties where waiting times exceed one year on average.

Take bowel cancer as an example. Under the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program, all Australians aged 45 to 74 are invited to complete a faecal occult blood test every two years. Yet after a positive result, many thousands of patients languish on outpatient public waitlists for months before seeing a specialist surgeon.

During this waiting period, much of the initial workup including blood tests, colonoscopy, and imaging, could be completed through public services or, for those with the means, privately, allowing diagnosis to be confirmed and treatment to commence without further delay.

Reimagining care through Advice & Guidance (A&G)

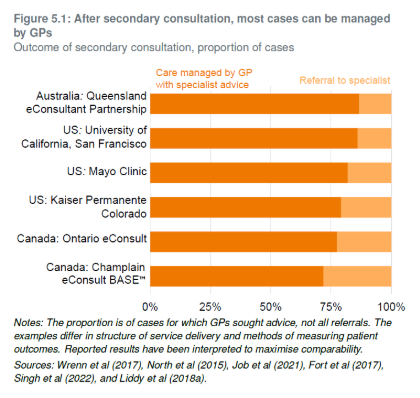

One of the most compelling recommendations in the report is the creation of a national “secondary consultation” or Advice & Guidance system. This is an evidence-based approach, one that our team has long championed in Australia and that has proven its value internationally.

A&G enables GPs and other primary care providers to obtain specialist input from secondary care before, or instead of, making a referral. This secure, two-way communication facilitates structured written clinical dialogue between GPs and consultants, supporting non-urgent patient care such as interpreting results, refining treatment plans, or assessing the need for further tests or referrals.

In the UK, A&G has been a cornerstone of outpatient reform for more than a decade.

In 2020-2021, NHS England reported that GP use of their A&G service almost doubled, with an estimated 1.58 million requests for specialist advice made. This prevented more than one million unnecessary outpatient appointments, eased pressure on waitlists, and enabled specialists to better triage and prioritise their time for patients with more complex needs.

Australia has seen promising examples of this approach.

At the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, the majority of outpatient specialist services provide Advice & Guidance as part of the referral process.

Subspecialist paediatricians at both the Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Sydney Children’s Hospital Randwick routinely provide A&G to referring clinicians, supporting the care of children across NSW Health and, at times, interstate.

In Victoria, Alfred Health and the Victorian Virtual Specialist Consults service, based at Northern Health, provide GPs with timely access to a wide range of adult and paediatric specialist outpatient opinions, streamlining care and reducing unnecessary referrals.

Finally, in Queensland, the Mater eConsultant service has delivered Request for Advice consultations between GPs and non-GP specialists for many years, providing timely, safe and cost-effective care for complex patients.

Queensland Health has led the way by introducing a statebased tariff for specialists providing timely advice — a pragmatic and sustainable policy that not only acknowledges the cost savings and improved outcomes achieved through early intervention but also sets a model for other states to follow.

In my own practice, I have seen firsthand how limited access to specialist care and prolonged outpatient waitlists can lead to delayed diagnoses, preventable complications, and poorer patient outcomes.

Take Lucas, an eight-year-old boy from a regional town with severe asthma. His GP is constrained by the current referral system, as are the emergency doctors who see him with each acute exacerbation. Lucas already has multiple specialist referrals in the system, each at various stages of being faxed and processed, yet there are no alternative services nearby to bypass the wait. Each time he presents to the ED, he is treated with short courses of oral steroids, discharged on the same preventer therapy, and sent home to wait for that elusive specialist appointment, still many months away. Each time, he risks another serious and potentially lifethreatening attack.

I often travel across the country to undertake visiting medical officer shifts in public hospitals, running outpatient clinics for cystic fibrosis and other chronic respiratory diseases. I like to think I am providing an additional value add service, but often when I arrive, it becomes clear that many of these patients do not need to be seen face-to-face.

For less complex cases, what I really need is access to their clinical history and a qualified healthcare worker locally, whether it is their GP, a hospital-based nurse consultant, junior doctor, or Aboriginal health worker, who knows the patient and can help facilitate their care and implement specialist recommendations.

If an A&G model of care were in place, I could engage remotely in a two-way dialogue with their care team to develop a locally delivered management plan with specialist input, avoiding unnecessary travel and clinic visits. This approach would also free up scarce specialist outpatient appointments for patients with the most complex or urgent needs.

Related

The way forward

The Grattan report offers a pragmatic roadmap: investment in underserviced areas, modernised care pathways, a secondary consultation system to reduce unnecessary referrals and stronger measures to address excessive fees.

Importantly, the Grattan report also sheds light on the economic model behind such reform. It recommends that each state government engage a public hospital to deliver secondary consultations, with specialists rostered to staff the system.

Grattan estimates that this model could provide at least 140,500 secondary consultations annually, avoid about 68,000 referrals across the public and private sectors, reduce wait times and save patients an estimated $4 million in out-of-pocket costs. In addition, around 4700 patients who might otherwise miss out would be appropriately referred for specialist care based on expert advice.

My only feedback of this otherwise timely and thoughtful report is that these figures are likely conservative.

International evidence, particularly from the NHS, suggests that when implemented well and supported by modern digital technology, the impact of such a model can be many times greater. This is a model that delivers faster access, more equitable care, and greater value for both patients and the health system.

Building an advicefirst healthcare system means creating digitally enabled referral pathways that provide timely access to specialist opinion. Such a model would enable patients to move safely between public waitlists, receive more effective management in the community, and, where appropriate, benefit from better utilisation of private services for faster diagnosis and treatment.

For patients like Lucas, this is about more than policy reform — it is about changing the course of their illness and, in some cases, transforming their lives.

Through an A&G model of care, his GP can seek specialist input without a traditional outpatient referral. I can remotely review his case, recommend stepping up his preventer therapy in line with national asthma guidelines, arrange lung function and allergy testing, provide tailored advice for managing future exacerbations, and coordinate a virtual followup with the local asthma nurse to support his family and school.

With rapid access to specialist advice, Lucas has avoided emergency departments, been spared hospital admission, had his treatment optimised close to home, and returned to school sooner. All of this takes minutes, not months.

Non-admitted services can no longer remain an episodic, referral-driven process. It must evolve into a system of dynamic, digitally enabled collaboration between primary and secondary care. By adopting these reforms, we can create a system that delivers on our shared goal of providing timely, equitable, and highquality specialist care for all Australians.

Associate Professor Vikram Palit is a paediatric respiratory physician, and CEO and founder of Consultmed.