Do we try to sew together a mass of emerging apps to connect and refer up and downstream, or use agile platforms that can connect it all in one system?

The federal government has drawn a line in the sand: since October 2025, pathology providers must upload reports to My Health Record by default, with diagnostic imaging following in February 2026. Medicare benefits are only payable when organisations comply.

That’s just the beginning.

The government is explicitly exploring ways to expand default sharing beyond pathology and diagnostic imaging to other types of key health information, including discharge summaries, specialist letters, and care plans.

It’s not a question of if GP consultations, specialist visits, and allied health services will face the same requirements. It’s when.

And it’s not just about uploading data. Since 2023, clinical software that connects to My Health Record has been required to meet mandatory security conformance standards.

While the government ultimately stopped short of mandating full Essential Eight compliance (recognising that very few systems would have met the threshold), the direction is clear: minimum cybersecurity standards are coming as a prerequisite for exchanging information with government services, including Medicare.

If your systems can’t demonstrate baseline security resilience, you won’t be connecting to national infrastructure much longer.

For organisations managing both internal health services and external community referral networks, this integration challenge isn’t theoretical. It’s the difference between being able to answer an auditor’s questions and hoping they don’t dig too deep and it’s a massive potential pivot to or away from productivity.

When audits expose the integration gap

The Australian National Audit Office’s recent audit of Defence health services put numbers to what many already suspected: poor integration between clinical and financial systems made it impossible to reliably track what services were delivered, by whom, or whether claims matched care.

Defence is far from unique.

The same pattern shows up across corporate health services, corrections health, employee assistance programs, and anywhere else an internal health service refers patients to external community providers.

What the audit exposed was that when you refer internally and deliver externally without a unified system, you lose the thread. You can’t track the referral pathway. You can’t validate service delivery. You can’t reconcile the claim back to the original clinical decision.

When the referral chain breaks

A patient visits an internal health service. The GP refers to a community specialist. The specialist orders pathology and refers to allied health. Someone else handles the follow-up. Each provider bills separately, through separate systems.

By the time finance tries to reconcile it all, tracking the chain of referrals feels more like forensic investigation than accounting. Clinically coded data lives in one system. Community provider billing happens in another. Medicare bulk bills go through one channel, private providers through another, and DVA or other contracted arrangements follow their own logic entirely.

When something doesn’t add up (and it often doesn’t), you’re left hunting through emails, spreadsheets, and disparate databases trying to reverse-engineer what actually happened.

For organisations with duty-of-care obligations, where you’re responsible for health outcomes even when care is delivered externally, that lack of visibility is a significant governance failure. But it’s one we’ve largely lived with because our systems haven’t been sophisticated enough to cope with the problem.

However, now that we can contemplate a system that doesn’t just connect these elements but in doing so also creates an audit trail, it’s not just governance people should be thinking about. It’s productivity.

Related

How much money and workforce productivity will start to emerge in our healthcare system when we start properly joining up all the elements of referral, clinical record, booking and invoicing, in real time?

We are literally talking in the billions. Yet it’s something people haven’t largely even contemplated in the current digital transformation of our healthcare system … yet.

How it should work

If your internal health service already uses a platform that manages referrals, clinical documentation, billing, and compliance, extending that same platform to community providers creates an unbroken chain of accountability from initial consultation to final payment.

Internal service creates a referral. The system captures the clinical justification, authorised services, and any service limits. The community provider receives the referral, accesses the same system, sees the referral context, and documents their service delivery. Service is coded and billed. The system automatically validates that the service matches the referral authorisation. Finance reconciles in real-time. Because everything lives in one system, there’s nothing to reconcile manually.

Every action connects to the one before it. The audit trail is automatic. The organisation maintains visibility and governance over care delivered externally, without sacrificing provider autonomy.

But the system pay-off is in productivity of the provider and the patient. Literally millions of hours not wasted in trying to connect the dots on payments, invoicing and bookings.

The pay-off is for everyone but providers will need to be able to extend the system they use internally to their external provider network.

Some systems today are starting to claim they can do this. But most only offer elements of solving the problem.

A cloud-based e-referral system, for instance, is neat but it can’t seamlessly integrate to bookings and invoicing in a line to create a single audit trail and set of invoices. These are nice-to-have new elements but they are essentially modern versions of the old SMD systems.

Solving the referral-to-community problem

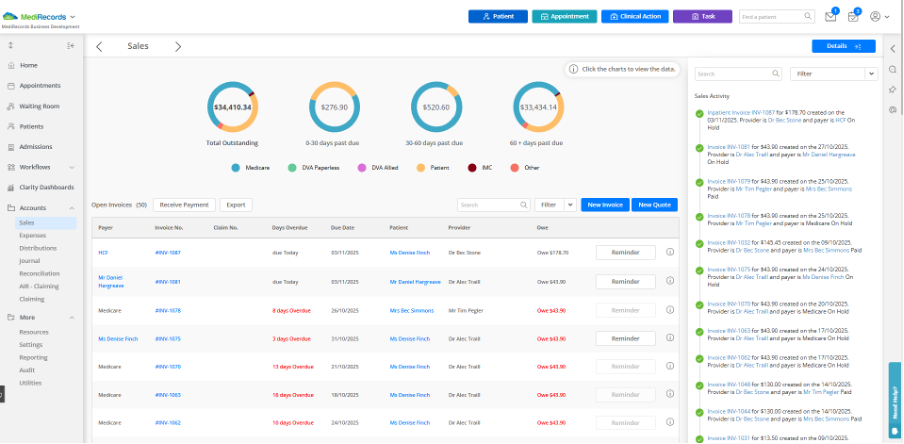

Forgive me here but I’m going to talk about the one system I’m involved with, MediRecords. I’m doing this because I know it so well , it provides a great example of what is achievable if you are able to extend your system seamlessly to external provider networks and, well, I’m selling it, obviously.

Surprisingly, given the seismic productivity gains on offer for both patients and providers, systems like MediRecords – essentially an FHIR-enabled cloud-based EMR with lots of good APIs – are, so far, few and far between in Australia.

For a long time the government has not really incentivised cloud-based connectivity in Australia with the result that many old server-bound integrations have been able persist a long time in the system.

Other cloud-based systems like MediRecords with longitudinal system connectivity capability do exist, but I’ll let you do that research.

What’s important is these new core cloud systems are agile in their ability to connect and share data in real time with other systems, which is auditable and which, because of the flexibility of connection, provides the ability for all elements of a single patient transaction to be captured and processed.

Where MediRecords is already deployed as the core system for internal health services, extending it to community providers means those providers gain access to the same platform, but with appropriate scope limits and data access controls.

A community GP sees only their own patients and referrals, but the referring organisation maintains oversight across the entire care pathway.

The platform handles referral management with structured referrals including clinical context, service authorisation, and validity periods. It manages multidisciplinary workflows with different claiming rules for GPs, specialists, allied health, pathology, and imaging. Real-time compliance happens automatically, validating services against referral authorisations and payor rules. And every referral, service, and claim comes with audit trails that prove clinical appropriateness.

For enterprise and community networks managing dozens of sites and hundreds of external providers, dashboards show where referrals are flowing, where services are getting stuck, and where revenue patterns don’t match clinical expectations.

Meeting regulatory standards

MediRecords supports FHIR and OntoServer standards, integrates with national infrastructure via secure messaging, and stores the structured data required for My Health Record uploads.

Under the hood, MediRecords is built with double-entry accounting, a general ledger, and full journal management. This provides the financial backbone that government finance departments and enterprise systems require.

The Department of Health, Disability and Ageing’s Compliance Strategy 2025-30 makes it clear: data integrity includes cybersecurity.

MediRecords’ cloud-native architecture aligns clinical and financial assurance with enterprise-grade security. For organisations evaluating community provider networks, that means one less integration risk and one less compliance gap.

The trade-off: Integration v independence

Requiring community providers to use a specific platform is less flexible than letting them use their own systems. Providers who’ve built workflows around their existing practice management software will need to adapt.

But the alternative (allowing disparate systems and then trying to create integration layers, data feeds, and manual reconciliation processes) recreates the exact fragmentation problem that audits identify, and incoming regulations will penalise.

It is all also holding back system productivity in possibly the most important area identified in all strategy analysis of our system: workforce.

The question for organisations managing referral networks isn’t whether to integrate. It’s whether you do so proactively, on your terms, with a platform you already understand, and which will deliver generational gains in organisational productivity, or reactively, under audit pressure, when you’re scrambling to prove compliance.

Using AI to scale compliance

When you’re managing thousands of services, including external referrals across hundreds of providers, manual review is almost impossible.

Some advanced providers, MediRecords being one of them, are exploring how artificial intelligence can automatically identify, link, and map services to item codes, validate claims against payor rules (whether government, insurer, or contract-based) and flag services that don’t match referral authorisations.

That means fewer manual audits, faster reconciliation, and better confidence that community providers are claiming appropriately. The result is a platform that doesn’t just capture data. It learns from patterns and helps organisations maintain governance without drowning in manual review.

What comes next

Health reform is heading in one direction: integration, data sharing, accountability and significant productivity gains, particularly in the area of workforce.

Organisations responsible for health outcomes are being asked to demonstrate traceability even when care is delivered externally and solve their productivity and workforce issues. That’s now just not feasible with legacy systems: when internal services and external providers use completely different platforms.

The path forward isn’t more integration layers, one-off cloud-based connection applications or complex data feeds. It’s system continuity.

Using the same platform internally and externally, so that clinical accountability, financial governance, and regulatory compliance flow naturally across organisational boundaries.

For organisations already using MediRecords internally, extending it to community providers isn’t just the path of least resistance. It’s the path of greatest assurance and productivity.

Connected care, credible claims, real compliance and generationally impactful productivity gains.

That’s what modern health governance and productivity looks like when care crosses organisational lines, which more and more these days it must if we are to manage a system rapidly moving to team based chronic care management.

Matthew Galletto is the CEO of MediRecords.

HSD publisher Jeremy Knibbs is a non-executive director of MediRecords.