A National Private Price — an independently set, nationally consistent, activity-based funding model for private hospitals — would go a long way to restoring balance.

Private hospitals in Australia are in serious trouble – not the kind of trouble that makes headlines every day, but the slow, silent, and devastating kind that leads to ward closures, staff cuts, and patients being pushed back into an already strained public system.

We are sleepwalking toward a national healthcare bottleneck, and the alarm bells are ringing loudly for anyone willing to listen.

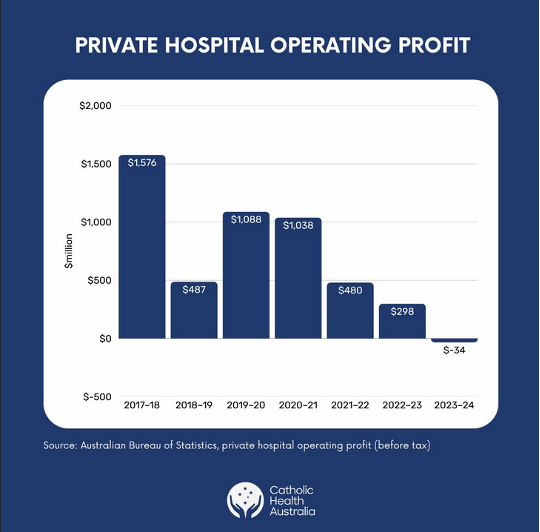

The latest figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics tell a sobering story.

Australia’s private hospital sector recorded a $34 million operating loss in 2023–24. Private hospitals have been bleeding slowly for years, but this is the first time on record that profitability has turned negative.

Those of us in the industry know this moment has been a long time coming. Over 80 private hospital services have disappeared in the past five years, and this number is continuing to grow.

Insurers will argue that as many services have opened as have closed. But replacing a maternity ward, perhaps the only one in a regional area, with a day-only joint replacement clinic is hardly a like-for-like exchange.

Meanwhile, health insurers are thriving.

In just one quarter last year, insurers made $581 million in profit. They are holding on to more than double the capital than they are required to by the regulator, and their management expenses — executive salaries, bonuses, and marketing costs — continue to grow each year.

Despite this, in the last quarter they returned only 78.3 cents of every premium dollar to hospital care. That kind of imbalance cannot be sustained and is an insult to every Australian paying their premiums in good faith.

This is not an abstract economic debate. Patients are already being affected.

Take Toowong Private Hospital in Brisbane for example. It specialised in mental health care for over 3000 patients annually. It closed its doors just weeks ago leaving patients with significant challenges now having to find care elsewhere, or more likely go without.

Related

Healthscope, a major player, is also collapsing due to a model that no longer holds. In many areas, public hospitals, already at breaking point, will be expected to pick up the slack.

Mental health and maternity services are at greatest risk — a finding confirmed by the government’s own review. They are expensive to provide and difficult to cross-subsidise in an environment of shrinking margins. Private hospitals are increasingly being forced to pull back from these essential areas of care.

It is the start of a domino effect. And once it begins, it is very hard to stop.

Private hospitals are not a luxury. They are central to Australia’s healthcare system. They deliver two-thirds of elective surgeries. They deliver acute and specialist care in regions that the public system cannot. They care for mental health patients, mothers, and people living with chronic illness.

Many of these services are provided by not-for-profit Catholic private hospitals, which reinvest every dollar back into the delivery of patient and community care.

If private hospitals continue to contract, public hospitals will be under even more pressure. Waiting lists will grow. Emergency departments will become more crowded. People in the regions will have to travel to the cities for specialist care. Resources will be stretched even further.

Yet too many people still treat the sustainability of the private hospital sector as a secondary issue. It is not. It is central to the future of accessible quality healthcare in Australia.

The problem is structural. The adversarial dynamic between hospitals and insurers is largely driven by a funding model that is broken. Contracts between insurers and hospitals do not reflect the true cost of delivering care. Inflation, rising wages, new technologies, and changes in patient expectations — none of it is accounted for.

Hospitals have little bargaining power. And no one is keeping insurers in check.

Some of the behaviour we are seeing from health funds would not be tolerated in any other industry. Last year, it emerged that some insurers were engaging in “phoenixing”, which is where old products are closed and reopened under a new name at a higher price, thereby skirting government oversight of premium increases. Gold-level cover, once the standard, has been priced out of reach. Silver is now the dominant product.

The introduction of the Gold, Silver, Bronze, and Basic classification system in 2019 was meant to simplify private health insurance for consumers. But the rise of phoenixing and the proliferation of ambiguous products like “Silver Plus” have had the opposite effect. We now have more than 25,000 products on the market, many of them barely distinguishable and increasingly difficult for patients to navigate. And nobody is watching closely enough to stop it.

There is also the slow creep of managed care. Insurers are increasingly directing patients into their own tightly controlled clinical pathways, cutting hospitals and doctors out of the process. While many hospitals have their own high-quality programs, insurers are increasingly refusing to fund them. This is not integrated care. It is insurer-controlled care. And it robs patients of choice.

We are drifting into a dangerous fiction: the belief that private hospitals will simply carry on, no matter how bad the books look. But they won’t. They can’t.

Healthcare providers do not run on sentiment or goodwill. They need skilled staff, modern equipment, and safe environments. That costs money. If the funding stops, the care stops. Not hypothetically. Not one day in the future. It is happening now.

This cannot be solved by tinkering. We need serious reform.

A National Private Price — an independently set, nationally consistent, activity-based funding model for private hospitals — would go a long way to restoring balance. Hospitals should be paid what it actually costs to deliver care. And insurers should be held to account for the return they provide on every premium dollar.

More broadly, it’s time to rethink the entire health architecture.

The National Health Reform Agreement, for all its importance, is effectively a public hospital agreement. It ignores the private system. It ignores primary care. And it fails to treat health as a unified national endeavour.

That must change. Commonwealth and state governments need to work together, not in silos, to build a truly national health framework.

We already know the diagnosis. The evidence is clear. What we need now is the treatment, and we need it urgently.

Because if private hospitals collapse, the damage won’t be confined to one sector. It will hit patients. It will hit public hospitals. And it will hit the very heart of Australia’s healthcare system.

Dr Katharine Bassett is a passionate health policy leader and the director of health policy at Catholic Health Australia, the nation’s largest non-government, not-for-profit network of health, community, and aged care providers.