Entrenched hospital overspends, rising demand and weakening fiscal headroom point to a system design that is no longer fit for the economic conditions it now operates within.

Australia’s hospital overspends are often framed as a failure of discipline or efficiency. They are neither. They are the predictable outcome of a health system whose economic foundations have shifted faster than its design.

That shift is no longer theoretical.

In late 2025, the Prime Minister publicly urged states and territories to “rein in public hospital spending” as a condition of maintaining long-term Commonwealth funding commitments. State health ministers pushed back, arguing that rising demand, complexity and access pressures cannot simply be controlled through tighter budgets alone.

That exchange matters. It signals that the long-standing tolerance for acute overspend – quietly absorbed year after year – is beginning to fray.

For decades, Australia could absorb rising health costs without confronting the structural weaknesses that drive them. That era is ending. What lies ahead is not just a tougher budget cycle, but a reckoning with how the system is commissioned, governed and led across its full continuum.

This article explains why hospital overspends became entrenched, why the old assumptions no longer hold, and how closing the commissioning gap between primary and secondary care offers a way forward.

How Australia papered over productivity cracks – and why it mattered

Australia’s long run of economic growth did more than raise incomes. It quietly shielded the health system from the consequences of weak productivity, allowing problems to persist without forcing real change.

From 2000 to the mid-2020s, Australia’s economy grew at around 2.5% a year on average – one of the strongest sustained growth records in the OECD. Over the same period, the United Kingdom grew at roughly 1.8% a year, while China grew far faster, at around 8% a year.

Those numbers can sound modest. Their impact is not.

Growth compounds. An economy growing at 2.5% does not simply add 2.5% once. It grows on top of itself, year after year. Over a quarter of a century, those differences determine how much inefficiency a system can tolerate before it is forced to change.

For Australia, this mattered in two very practical ways.

First, steady domestic growth expanded the tax base. Second, China’s rapid rise delivered a once-in-a-generation external windfall through exports, with China accounting for around one-third of Australia’s total goods exports at its peak, driving the largest terms-of-trade boom in Australia’s history.

Strong national averages have long masked deep inequities in access and outcomes. Together, these forces created fiscal headroom. Governments could keep spending more without confronting underlying productivity problems across public services – including health.

Health was a major beneficiary of this settlement. Australia continued to deliver strong average outcomes – consistently ranking in the top tier of OECD countries on measures such as life expectancy and avoidable mortality – even as productivity growth lagged behind comparable economies. But those averages have long masked profound inequities, particularly for people in rural and remote communities and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who experience markedly poorer access, outcomes and life expectancy.

The economy’s capacity to absorb rising costs reduced the pressure to confront either problem directly: inefficiency in how the system was designed and delivered, and inequity in who benefited from it.

That protection came at a price. It delayed reform.

Overspends could be covered rather than fixed. Pressure could be managed with more funding instead of changes to how care was planned, commissioned and delivered.

Strong growth didn’t fix Australia’s health system. It postponed the moment when fixing it became unavoidable.

Why other systems hit the wall earlier

Not all systems had that luxury.

The United Kingdom, operating with weaker long-run growth and tighter fiscal constraints, ran out of room much earlier. Following the global financial crisis, health spending came under sustained pressure amid a decade of fiscal consolidation, forcing earlier and more difficult confrontations with productivity, integration and system accountability.

Australia deferred those decisions. The capacity to spend delayed the need to redesign.

When hospital overspend becomes normal

This long period of economic insulation shaped behaviour inside the health system.

Healthcare now absorbs a large and growing share of public expenditure. Within that envelope, acute care overspends at the state level have become a recurring feature of budgets.

Year after year, hospitals exceed targets. Year after year, those overspends are covered.

This tolerance has not been neutral. Overspends were managed through supplementation rather than correction. Structural weaknesses were accommodated rather than addressed. Acute services continued to dominate decision-making not because of bad intent, but because the system remained organised around hospital activity, crisis response and risk containment.

This is the bridge between economics and hospitals: Australia’s long growth dividend allowed acute overspends to be tolerated rather than fixed, embedding behaviours that now drive costs faster than revenue can sustain.

The commissioning gap at the heart of the problem

This is where the commissioning gap between primary and secondary care becomes decisive.

Primary care in Australia is largely funded by the Commonwealth – through Primary Health Networks and direct payments to providers such as general practice and allied health. States, meanwhile, fund and operate hospitals and most secondary care.

Between these two funding and accountability streams sits a structural gap.

While formal State-Commonwealth agreements and governance mechanisms do exist, there is no strong, system-level arrangement that operates day to day to align Commonwealth-funded primary care with state-funded secondary care around shared demand management, outcomes and patient flow.

That gap at the national level cascades down to regions and places, leaving Primary Health Networks, local health services and providers without a clear mandate or authority to jointly manage demand or own outcomes across the continuum. As a result, no single actor controls demand, and no one fully owns outcomes.

When upstream care fails to prevent, divert or manage demand, hospitals absorb the pressure. They become the shock absorber of last resort.

Related

What this looks like when it is done properly

This is not theoretical.

We have seen these principles applied in practice through long-term reform efforts that deliberately aligned commissioning, accountability and system leadership across primary and secondary care – including the five-year health system reform journey supported in Manitoba, Canada. That work focused on building shared stewardship for population outcomes, strengthening commissioning capability, and shifting decision-making away from acute dominance towards whole-system performance.

The lesson from that experience was clear: when responsibility for outcomes is genuinely shared across the system, hospitals stop carrying the burden alone – and cost, access and quality can be addressed together rather than traded off against each other.

The pandemic proved change is possible

There is an important recent counterpoint to the idea that health systems are simply too complex to change.

During covid, Australia’s health system transformed care at breakneck speed. Telehealth was rolled out nationally in weeks. Funding rules were rewritten almost overnight. Workforce models shifted. Data sharing and service redesign accelerated at a pace that would previously have been dismissed as impossible.

This did not happen because the system became simpler. It happened because the case for change was undeniable, and leaders acted.

That experience matters. It shows that the constraints often cited as reasons for inaction are not immutable. They are conditional.

From inside-out to outside-in leadership

What is missing now is not capability, but alignment and intent.

Structure alone will not deliver reform. What is required is a guiding coalition of care – a shared leadership compact across primary care, community services, hospitals and funders that accepts collective responsibility for population outcomes, demand management and system flow.

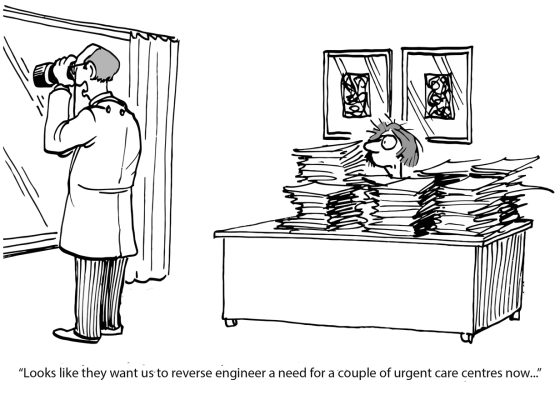

Australia has adopted the language of collaborative commissioning, but execution has been shallow. Without deeper cultural change, acute services continue to dominate decisions. The system still operates with an inside-out mindset, starting from institutional capacity and budgets, then working outward to justify demand.

What is needed instead is an outside-in population health management mindset: starting with cohorts and needs, understanding how demand is generated across the life course, and deliberately shaping upstream investment to reduce avoidable downstream pressure.

Why this article exists

Australia’s current health system challenge is not as dramatic as a pandemic, but it is no less serious.

Entrenched hospital overspends, rising demand and weakening fiscal headroom point to a system design that is no longer fit for the economic conditions it now operates within.

This article is intended to help make the case for change – not through alarmism, but through clarity. It brings together the economic context, the structural drivers of hospital overspend, and the commissioning gap at the centre of the problem. And it points to a pathway grounded in experience, not theory.

Australia has already shown it can change its health system when it must.

The pandemic proved reform is possible. The economic trajectory now shows it is necessary.

What would change if we designed Australia’s health system around people and place, rather than institutions – and started measuring success accordingly?

Three questions leaders are now asking

Why do hospital overspends persist even after repeated efficiency drives?

Because efficiency inside hospitals cannot offset demand generated outside them. When prevention, primary care and community services are weakly commissioned or poorly connected, unmet need escalates into acute care. Hospitals then carry the cost of upstream failure, regardless of how efficiently they operate.

If State-Commonwealth agreements exist, what is actually missing?

What is missing is an operational mechanism that works day to day, particularly at a regional level, to jointly manage demand, outcomes and patient flow across primary and secondary care. Existing agreements allocate funding and risk between governments, but they do not create shared accountability for system performance where care is planned and delivered.

How does this argument relate to equity, not just cost?

Systems designed around institutions tend to underserve people furthest from them. Weak commissioning across the continuum disproportionately affects rural and remote communities and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Commissioning by cohort and place, with shared accountability for outcomes, creates stronger foundations for both equity and sustainability.

Jay Rebbeck is CEO of Rebbeck, working with public-sector leaders to create brilliant services and thriving communities through commissioning excellence.

This article was originally published on LinkedIn. Read the original here.